To the first point, the Christian tradition denies that God’s existence is obvious, in the sense of self-evident. If God – an all-powerful, all-good, eternal being who created the universe – exists, wouldn’t it be obvious? Or, from a different point of view, doesn’t belief in God’s existence properly belong to faith, and so isn’t it pointless, or even an impiety, to try to prove it by reasoning? Or, from yet another line of approach, aren’t philosophical arguments like this futile? Haven’t people been arguing these questions for centuries with no clear winner? There are some who see arguments for God’s existence as quixotic, and this can be for different reasons. In this book, Feser puts forward five arguments of this type and defends them against critique.īefore proceeding to outline the arguments in question, it might be worthwhile to clear the ground of a few possible misgivings.

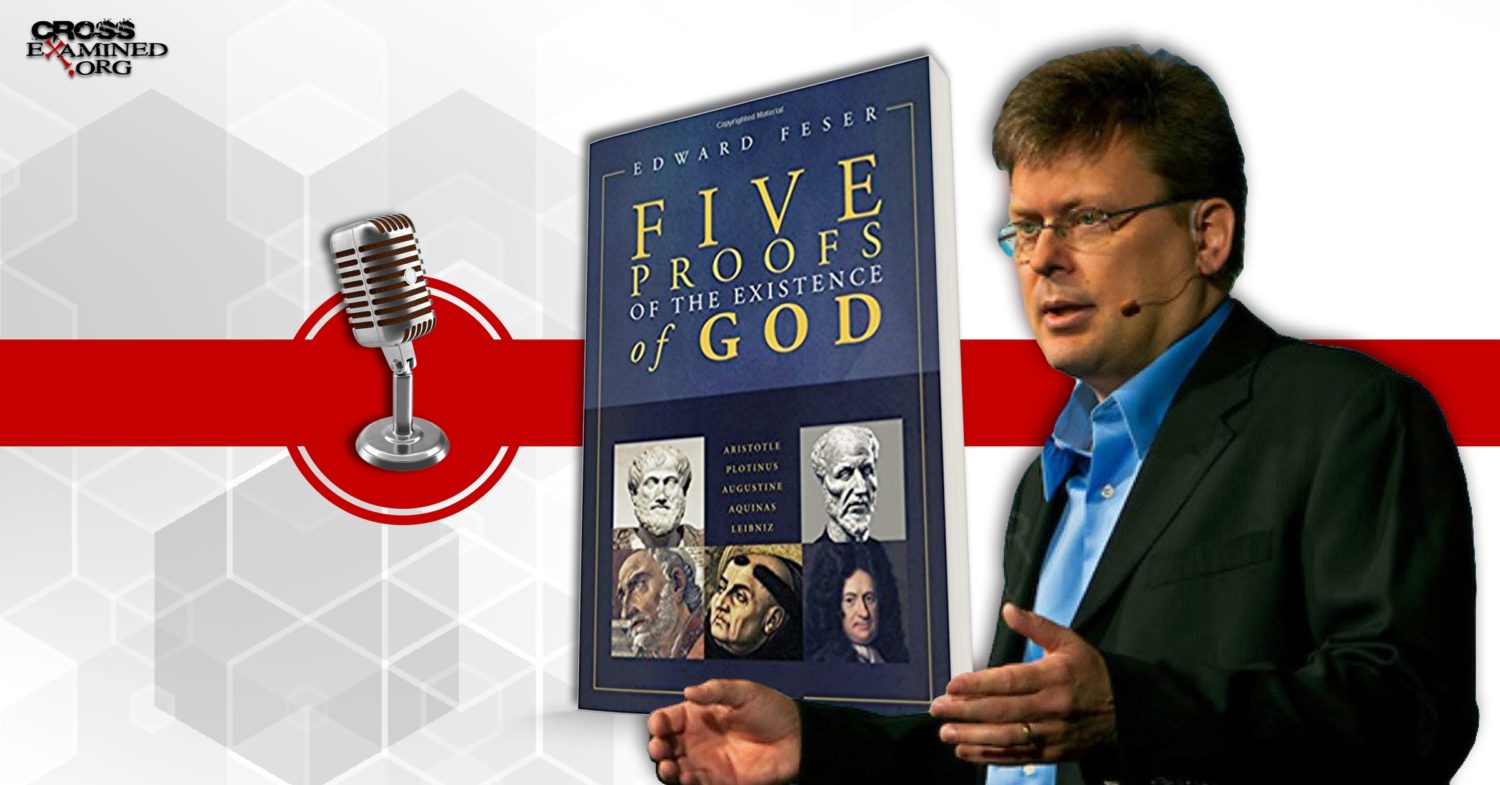

But there is a class of arguments which are deductive in form and proceed from premises which are difficult to deny these arguments claim to be demonstrations of God’s existence - “proofs”, to use Feser’s word. Some of the arguments are probabilistic and lead to the conclusion that God’s existence is likely arguments proceeding from observations of particular features of the world, such as the argument from design, are of this kind.

As a group, they proceed from a variety of different premises, and, naturally, particular arguments are convincing only to those who accept the relevant premises. You have your cosmological argument, your ontological argument, your argument from design, your argument from moral objectivity, your argument from Bach – a personal favourite of mine - and many others. Arguments for the existence of God are of perennial interest, and over the centuries many different lines of reasoning have been proposed.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)